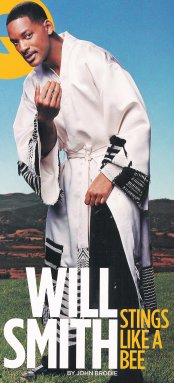

The Contender

In the role of his lifetime, as Muhammad Ali, Will Smith laces up his gloves for an Oscar shot

By John Brodie

When James Earl Jones hung out with Muhammad Ali as part of his preparation for playing a character based on Jack Johnson in the 1970 film The Great White Hope, Ali likened himself to that turn-of-the-century black champion who enraged the powers that be. "I grew to love the Jack Johnson image," Ali told Jones of the fighter who dated white women and was sentenced to prison in 1915 for violating the Mann act. "I wanted to be rough, tough, arrogant, the nigger white folks didn't like."

Will Smith has made a fortune being the African-American white folks love--arguably the country's first postracial superstar, who surfed the suburbanization of rap from a lower-middle class upbringing in West Philadelphia to Hollywood's inner circle of $20 million leading men. But later this month, his reputation as a dramatic actor will be on the line when he plays Ali, a sports hero to most of the world but a patron saint to African-Americans.

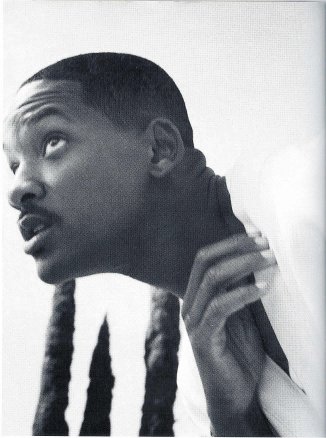

"You can't mess it up," says Smith of what's at stake as we sit on the verdana of Sherwood Country Club in Thousand Oaks, California. "You don't even want to think about the ramifications of doing a bad job." Smith orders a chamomile tea and a five-egg-white, one-yolk scramble, then adds, "I spent five years turning the movie down, thinking about the negatives. I questioned my ability for a good five years." Here above lush fairways, Smith, dressed in white linen pants and a brown polo shirt, blends in with a membership that includes Wayne Gretzky. But the 33-year-old actor looks different than he did the last time audiences saw him, in The Legend of Bagger Vance. For Ali, he bulked his six-foot-two frame up to 212 pounds. And the mustache he is sporting today, grown for reprising the role of Agent J in this summer's sequel to Men In Black, gives him the look of a Dark Gable--an epithet the young Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. used to describe his own good looks. Beyond these physical changes, however, Smith is less whimsical than in the past. He is polite, articulate and funny at times. But transforming himself into Ali has also given the man who ushered in Y2K by dubbing it the Willennium a gravitas, something that is evident when he talks about how he let his fans down with his last two films.

Many of those fans have been following Smith since he released his first album, during his (and their) senior year in high school. As the latter half of DJ Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince, he made (and squandered) a fortune built on bubblegum rap like 1988's "Parents Just Don't Understand." After Quincy Jones picked up on Smith's devil-may-care yet squeaky-clean persona, he pushed the artist to star in The Fresh Prince of Bel Air. In 1993, Smith broke into movies as the gay con man in Six Degrees of Separation after playwright John Guare spotted photos of Mao, Malcolm X, and Run D.M.C. on Smith's dressing-room wall and announced, "You're him!" Two blockbusters--Independence Day and Men In Black--followed, in which Smith could be counted on to save the world with a grin.

The bond between the actor and his audience frayed, however, with Wild Wild West (dubbed "a comedy dead zone" by Roger Ebert) and Bagger Vance, in which he starred with Matt Damon. On the latter, his worst fear--that his character would be seen as yet another of Hollywood's Magical Negroes (cf. The Green Mile's Michael Clarke Duncan and Family Man's Don Cheadle)--was realized. "Using golf as an analogy for the concept that you can't have any fear about the outcome of an undertaking attracted me to Bagger Vance," says Smith. "But I knew going in that black folks just generally don't enjoy watching films about that era. Black folks don't like seeing black folks catering to white people."

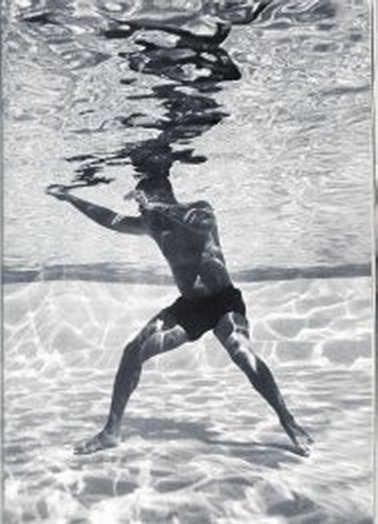

Portraying Ali could not have been a more radical departure from Driving Mr. Damon. Taking the role would involve a physical and spiritual transformation. With no stunt double or trick camera work to fall back on, Smith would have to learn to box well enough to stay in the ring with a succession of modern-day fighters who would play Ali's opponents: Sonny Liston, George Foreman, and Smokin' Joe Frazier. Tougher still, Smith would have to convincingly relive the spiritual odyssey that led to the heavyweight champion's putting Allah before country, refusing induction into the military in 1967 and uttering the most famous double negative in boxing hisory: "Man, I ain't got no quarrel with them Vietcong." Until the actor met with Michael Mann, the director of the picture, he could not even envision playing Ali. What changed his mind was a three-hour discussion with the director of The Insider in winter 1999. "It was one line," says Smith as he orders a second pot of tea. "Michael said, 'I will create a curriculum that will allow you to create Muhammad Ali inside you.' And I said to myself, 'OK, I can study hard.'"

Hollywood was skeptical. With the exception of his character in Six Degrees, Smith had never disappeared inside a role. Depicting Ali's playfulness and posey in verbal sparring sessions with Howard Cosell (Jon Voight) would be within his grasp. But he could project the inner strength of a man who could withstand a pummeling by George Foreman and being stripped of his heavyweight crown?

When I ask Smith if capturing Ali's grit is where he felt the most overmatched, he responds quietly but firmly, "That's the aspect of my personality people don't generally see. That's not what I get paid for." For behind the jug ears is a man who thrives on discipline and relishes the opportunity to show the world a resolve that his intimates have known for years.

Sam Cooke's "Bring it on Home to Me" plays as Smith, looking eerily like a 22-year-old Cassius Clay, hits the speed bag in Miami's Fifth Street Gym. The movie opens in 1964, days before Ali's title shot against Sonny Liston. As Mr. Soul croons, I'll give you jewelry and money too, Smith propels the bag with his fists: thwackety-thwackety-thwack. Suddenly, the film cuts to a black boy staring at a white Jesus in a church. More thwackety-thwackety-thwack, and that boy is now a man in a mosque, listening as Malcolm X (Mario Van Peebles) preaches that he's tired of begging to sit at the white man's lunch counter.

The weigh-in. Liston and Clay circle each other, and the Louisville Lip starts running off at the mouth. But Liston, as played by Michael Bentt, the former WBO heavyweight champ, stops him cold. Bentt has captured the unrepentant menace that was Liston, a man who jumped rope to James Browns "Night Train" and died on the wrong end of a needle. As Bentt brushes by the challenger, he growls, "I'm gonna beat your ass like I was your daddy." Smith's face registers fear for a second. But then his eyes light up with Ali's impish twinkle, and he spits out a flurry of rhyming insults to the throng of assembled reporters: "You want to lose your money? Bet on it Sonny!..."

The opening bell. In the early rounds, Smith takes a barrage of body blows. The fight is not the expressionistic black and white of Raging Bull, though. The battering Liston gives Clay's solar plexus looks more like something on pay-per-view, something real. This is a new type of boxing picture. If Scorsese's paintings--brutal but arty--Mann is going for a Weegee photograph, crisp, haunting, but not oversold. "I love Raging Bull and a lot of the things Scorsese did," Mann tells me one day this past September when I stop by the editing room to watch his footage. Much as he admired Jake LaMotta's journey to what he dubs "a flawed redemption," Mann wanted his picture to be a departure from previous boxing pictures. "While Raging Bull is experientially handled," he adds, "we went for a heightened authenticity."

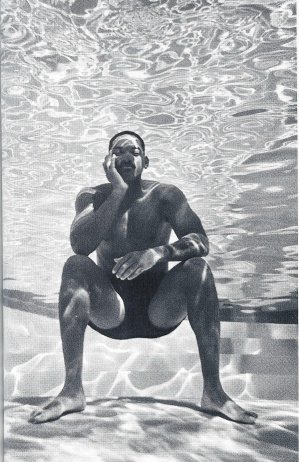

To attain authenticity, Smith spent six months, beginning in August 2000, at a fight camp. The Ali production team converted a Santa Monica garage into a boxing gym. Here the star learned to box in the company of professional fighters (four world champions among them). To honor Ali, they would not pull punches on the leading man. Bentt, the son of Jamaican immigrant, coined the camp's mantra: "Iron sharpens iron." His strategy was to nurture Smith but not pamper him. "You can't play a character like Ali without experiencing some kind of pain," he says. "You have to be true to the journey."

Once Smith had mastered the fundamentals, he was ready to spar. But there was only so much time to teach him the lessons the pros had learned as kids. ("If I had gotten Will early on, I could have made a fighter out of him," notes Ali's trainer, Angelo Dundee, who worked with Smith for the movie.) On Thursdays round-robins were held in which one fighter stayed in the round for six rounds, facing a different opponent in each. One Thursday when Smith was in the ring, the other fighters played a joke: When the bell rang for round four, Smith looked across the ring and saw Sugar Ray Leonard.

"Come on big fella," said Leonard as he danced toward Smith. "Let me see your jab."

"My jab is perfectly fine. Stuck to my chin, protecting it right now," was the actor’s response as he tried his best not to get banged up by the former champ.

Beyond Leonard, there was another great fighter: Ali came to the camp last fall. And as the former champ, dressed in a tracksuit, entered, Smith went into character.

"You ain't pretty enough to be in here with me. You taking' away from my pretty," he yelled his beat approximation of Cassius Clay. As Ali stared at this younger version of himself, he smiled like a kid at a magic show. Impressed with what he saw--but not willing to be upstaged by the pretender--Ali turned to his lifelong friend Howard Bingham and quipped, "Man, how come you ain't tell me how crazy I was when I was young?"

The gym erupted with laughter--but went silent when Ali climbed into the ring, laced up his gloves and half-playfully, half-genuinely traded punches with Smith. Tempting as it might have been to put a hurting on the Greatest, the actor knew better. "Ali weights 250 pounds and still knows how to punch," says Smith as we leave the breakfast table and head for the parking lot. "His punches aren't as fast. But if he punches you in your face, he can knock you down. So I'm thinking, I hope he knows we're playing."

Filming the bouts was brutal. The movie covers Ali's career from the Liston bout through the 1974's Rumble in the Jungle, and getting the right images required shooting a sequence ten of fifteen times, so that the fighter on the losing end of a round would have to take the same beating over and over (pity the fool who played Jerry Quarry). For Smith, the worst day was what he dubs Joe Frazier Left-Hook Day. Since Dundee trained Smith to fight like Ali, Ali's weaknesses, such as dropping his right hand, became Smith's. And fighter James Toney's simulation of Frazier's style meant Smith would be in for a beating when they re-created Frazier's fifteen-round victory over Ali at Madison Square Garden.

Fights were shot chronologically, so the physical punishment on Smith increased over the duration of the production. For as Ali aged and lost some of his ability to dance, he took more lumps. Although Toney gave Smith his worst single day in the ring, the actor claims the most painful week in his life came at the hands of Charles Shufford, the pro heavyweight who played George Foreman. The title bout in Zaire that provides the movie with its dramatic conclusion was one of Ali's most punishing, as he absorbed hit after hit, rope-a-doping Foreman until he could deliver the coup de grâce in the eighth. The last thirty-two seconds of the fight was shot over five days. "Your body starts doing really weird things when you get a beating like that," admits Smith. By "weird" he means sitting in the corner between rounds and watching one of his legs shaking uncontrollably. Beyond the odd tremor, the only injuries he sustained during the entire shoot were a busted thumb and a bruised rib. But anyone who suspects punches were pulled in the making of the movie need only to watch the final round in Zaire sequence to know that Mann succeeded in capturing "heightened authenticity." When Smith hits Shufford with a knockout punch, Shufford's face literally buckles around Smith's fist. There are no special effects. Indeed, a few days my breakfast with Smith, I bumped into Michael Olajide Jr. on the Fox lot. Olajide is a retired fighter who worked on the movie. I asked him how many takes were required to get that shot. Olajide shook his head and then said, "Nineteen. Charles had to go down nineteen times."

Cruising through the valley in Smith's red Bentley coupe seems as good a time as any to talk about the Islamic faith. The car costs what most people put down for a house and boasts a burnished-wood dash, soft leather seats and tinted windows to cut the glare of the afternoon sun that streams down the gated the communities of Chatsworth. Will's 8-year old son from his first life, Willard Christopher Smith III (known as Trey), is in the backseat.

Smith has known Muslims since he was Trey's age. Seven of his ten closest friends from childhood are Sunni Muslims or Nation of Islam, the Chicago-based sect headed by Louis Farrakhan. Though Smith keeps a Koran and a prayer rug in his house, he was raised Baptist. He believes in God but has never been a fan of organized religion's "exclusionary nature." "I believe in God the way that Christians, Muslims, Jews and holy people of the world believe in God," he says.

To prepare for playing Ali, he decided to "reverse engineer" the boxer's spiritual journey, first studying Orthodox Islam with a Muslim cleric named Munir. Next he learned about the rift between the Nation of Islam's Elijah Muhammad and Malcolm X, a split that forced Ali to choose between two men he admired. For Smith, the key was to understanding Ali's awakening in the '60s came from Geronimo ji Jaga, formerly Geronimo Pratt. "I'm from the hip-hop generation," says Smith of the sociopolitical reeducation he received from the Black Panther. "We got cars and money and jewelry. Whereas in the '60s, war had been declared on black America. It becomes very clear why Ali wasn't going to war. You look back at hoses and dogs and billy clubs--that's war! We were at war. And why would I go fight elsewhere if my women and children aren't safe here if I leave?"

In addition to bringing an understanding of Islam to his role as Ali, Smith brought his own experience to his portrayal of what he calls Ali's "complex" relationship with women, one he feels has more to do with an "attraction to femininity" than being a "womanizer hound." The movie depicts three of Ali's four marriages, and Ali told Smith he didn't want a biopic that idolized or sanitized him. "Just tell the truth" was the only advice he gave the actor.

Smith was divorced from Trey's mother, Sheree Smith, in 1995. Two years later, he married Jada Pinkett. With her he had his second son, Jaden, and his only daughter, Willow. Smith applauds his wife and ex-wife, who lives twenty minutes from him, for being able to get along and raise their kids together. But he credits Quincy Jones for guiding him through an amicable divorce. "Quincy said, 'She's going to be there every Christmas, every Thanksgiving. Give her 20 percent more than what she asked for and move on with your life.' But I couldn't do that, so we fought for a little while," says Smith.

The performer kept his copyrights, his production company, his real estate company and the house. Sheree got $900,000 in cash, $250,000 for a down payment on a new house, child support and two Mercedes. They share custody of Trey. With Trey, for whom he wrote the rap version of "Just The Two of Us," he seems genuinely torn between doting and disciplining. In a refreshingly old-school manner, he corrects his son's diction and tries to instill in him the ability to think critically. Papa is all about strength and discipline. "I want to despise weakness. Weakness feels like cancer. If someone around you is weak, eventually they'll make you weak."

His father, Willard, an air-conditioning and refrigeration-system repairman, and his mother, Caroline, a school-board employee, ran a tight ship for their son, his older sister his twin younger sister and brother. Growing up, Smith wore a uniform and took a forty-minute bus ride to a predominately white parochial suburban school. (In tenth grade, he changed to the local public high school, which had a great number of African-Americans.) Rather than lavish gifts on Trey, as many divorced dads do, Smith tackles projects with him. For the boys eighth birthday, Smith threw a red-carpet premiere of a home movie, The Trey Tricks, at his Malibu Canyon ranch. (Smith's main residence is a 4,900-square-foot hacienda in Thousand Oaks with a pool and a par-3 hole for practicing golf.) Keenen Ivory Wayans and Eddie Murphy came and watched Trey portray a superhero with magical powers. Smith played an evil warlord who kidnaps Trey's stepmother and brother. Trey's mother played a spiritual guide, an Obi Mom Kenobi.

Along with Quincy Jones, Wayans and Murphy are part of Smith's kitchen cabinet. ("They broke in when there was no room for them to break into Hollywood," he says, "so they are much more aware about the grit and the grime of the business.") The Artist Formerly Known as the Fresh Prince is not without his share of lessons about the hazards of a new fortune. By the time he was 20, he had made and squandered his first million on cars, designer shopping sprees and a subsequent six-figure IRS bill. However, it was Murphy who called Smith from the I Spy set in Budapest on September 11 and told him to figure out the right moment to use his celebrity to help the country. The opportunity arose when Dream Works cofounder Jeffrey Katzenberg called Smith about being involved in the September 18 telethon.

Smith and Ali's subsequent appeal for tolerance was a profound moment in the otherwise surreal TV special (Yo, this is Sly Stallone. How much ya wanna pledge?). Trying to dissuade Americans from the misperception that all Muslims hate the United States was for Smith "the first time in my life I actually felt I did something important." When I ask him how he thinks audiences will, in the wake of September 11, perceive a film with a Muslim as its hero, he rope-a-dopes me, suggesting that he hasn't thought about the box office. "I'm really glad I have Ali coming out right now, a film that does have an important message at it's core and spirituality and emotionally, and a film that has a deeper meaning you can come away with. 'Cause I...if I had another type of movie coming out right now, I'd feel completely worthless."

Ali's religion may have no effect on the box office. In this day and age, most people think of him as a Parkinson's-riddled ex-fighter. His politics are as forgotten as his raps. The same folks that paid to watch Ali float like a butterfly on a closed-circuit television in the '70s may show up to watch Mann's rendering of the superfights. Simultaneously, the same fans who remember nodding in sly approval when the Fresh Prince busted his rhymes over the I Dream of Jeannie theme may turn out, too. Current events could overtake the movie in such a way that critics and Op-Ed writers start tossing around words such as prescient. Then Smith's journey from Thousand Oaks in 2001 to Miami in 1964 will have been worth it, especially if he gets to dance onstage at the Oscars and shout his best approximation of the young Cassius Clay, "I'm 33. Ain't a mark on my face, and I'm king of the world."